School districts and libraries are in the midst of a surge in requests to ban certain books from bookshelves and classroom curricula, stemming from a small but vocal group of conservative politicians and activists. Many of the books in question feature topics related to LGBTQ+ people, people of color, or other marginalized groups.

What’s behind the surge in banned books?

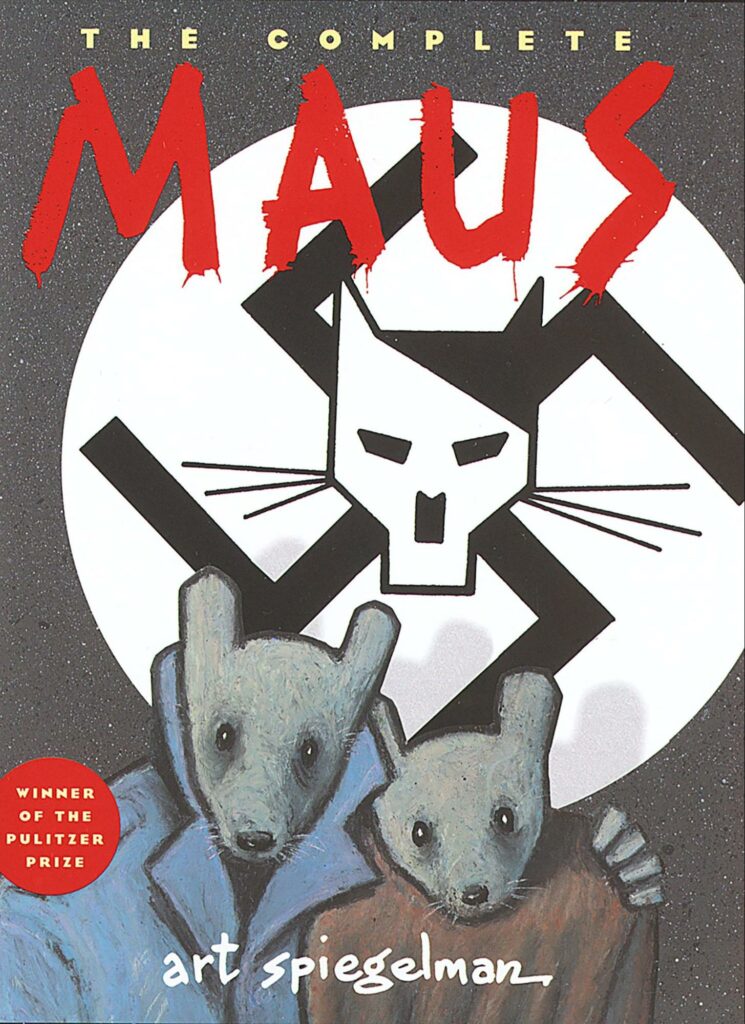

The most recent book bans have received a lot of media attention. In Tennessee this year, a school board voted unanimously to remove Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel “Maus” from an eighth-grade curriculum—an unflinching depiction of the Holocaust. The school board cited the brief nudity of cartoon mouse characters and eight instances of foul language (most of which are mild enough to be allowed on prime time TV) as some of the reasons why the book should be pulled from the curriculum.

Texas is now a main battleground in the current wave of book challenges, with hundreds of books being pulled from shelves across the state to be reviewed. To add to the spectacle, a church in Tennessee held a book burning earlier this month, in which “accursed items” like “Twilight” books were torched.

These book bans are not unprecedented, and have flared up throughout history depending on the political climate and context. For example, in the early 2000s, the “Harry Potter” book series sparked a conservative backlash that prompted challenges to the books in school libraries across the country, and book burnings.

Why is banning books harmful?

Parents and teachers are pushing back against the book challenges, and speaking out about why banning books with controversial or difficult content is harmful to children. A viral Twitter thread by Gwen C. Katz laid out one line of reasoning for keeping “Maus” and other challenged books in schools. “The broad trend is destruction and recreation of history: The actual events, as narrated by the people they happened to, are declared unacceptable in their current state, and are replaced with books tailored to modern sensibilities, which are then declared the ‘correct’ account.”

Katz explains that substitutes for these banned texts are usually fictionalizations that remove the account from people who actually experienced the events, and often soften and sanitize the more unpleasant details of historical atrocities for the sake of being more appealing to a broad audience. The replacement texts often lack the specificity found in the banned books—powerful first person stories and real accounts are replaced with gentler fictional stories and fables about all forms of bigotry or injustice, rather than the specific one being taught. “But the actual effect is to blunt and erase the atrocity,” explains Katz.

Books like “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas” by John Boyne are often taught in place of banned stories about the Holocaust. Stories like this one are told from a position of “innocence,” from the point of view of people who did not participate in or even know about the events in question, because that’s deemed less troubling for kids (and their parents). However, that point of view fails to demonstrate to kids that real people really did commit terrible acts of injustice based on prejudices, and that many of those extremely problematic views still exist today.

In the “appropriate” substitutions, “Bad things can happen, but only abstractly” says Katz. The terrible events and outcomes are glossed over or sanitized so that the impact is completely lost on the reader.

A historical atrocity can never be a metaphor for all bigotry because the specifics are what makes it an atrocity. The Nazis didn’t just do ‘bad things, generally,’ they did THESE things. And leaving out the details is simply historical erasure.

Gwen C. Katz

Many argue that presenting challenging content to children in the context of literature is a safe way to open up conversations with them about difficult topics, especially in the safe environment of a classroom with a knowledgeable teacher to help them understand and process what they’re learning. Reading depictions of sexual situations, violence, suicide, racism, or other frequently banned types of content, can give young readers the vocabulary to talk about topics that may otherwise be hard for them to address.

Which banned books should my family read?

- This graphic novel uses animal characters to portray the events of the Holocaust, as told by Spiegelman’s father, a survivor of the Aushwitz concentration camp. The book is a great way to open up a conversation with your family about what happened during the Holocaust and what genocide means. (Age 11+)

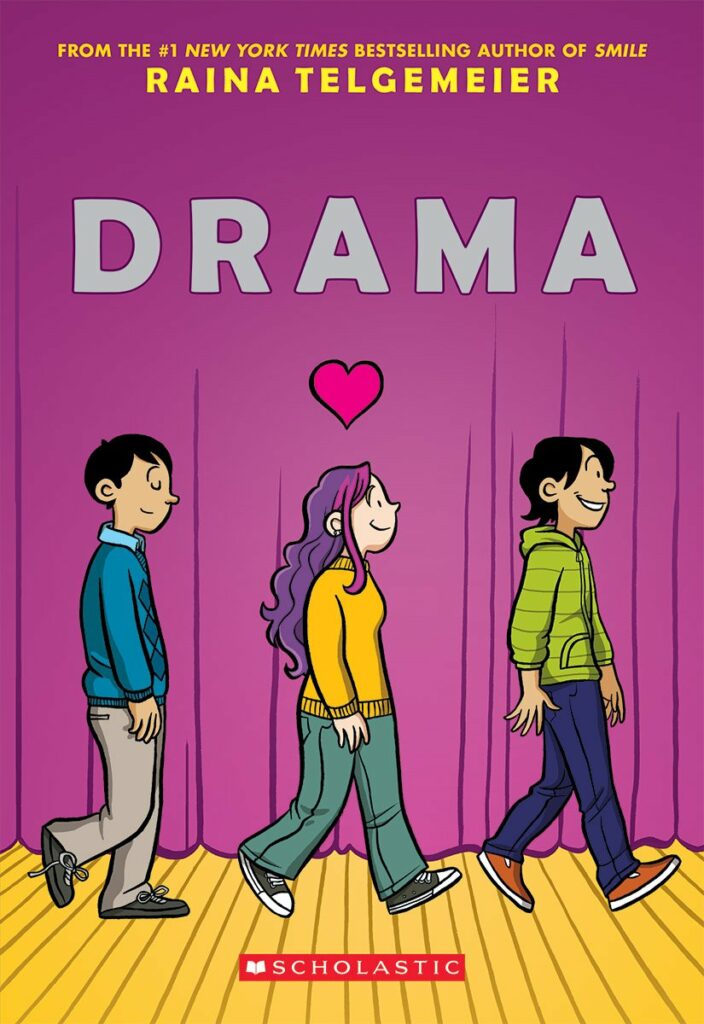

2. “Drama” by Raina Telgemeier

- Another graphic novel—”Drama” follows the story of a middle school musical, while focusing on the complex lives of young LGBTQ+ characters. This book has been challenged in some schools because of it’s honest look at teens questioning their sexual identity. (Age 10+)

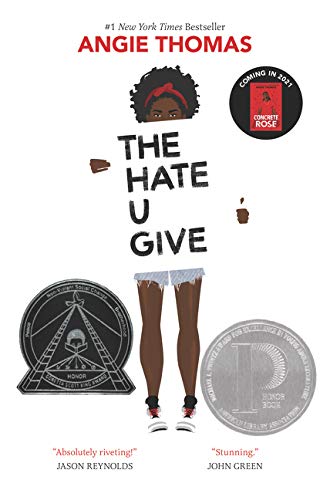

3. “The Hate U Give” by Angie Thomas

- This young adult novel is about a police shooting of an unarmed Black teen and has been pulled from school library shelves for reasons such as profanity, racial slurs, and content about substance abuse. With its bold confrontation of police violence and systemic racism, this book is a good one to read with teenagers to get a conversation started about the Black experience in the US. (Age 13+)

Originally published as “George”—“Melissa” is a children’s novel about a transgender child in the fourth grade. It was among the most challenged books of 2020, simply because it portrays a trans child. It’s important for kids to read stories about all types of people, and sharing trans stories can help kids empathize with people with all types of gender identities. (Age 10+)

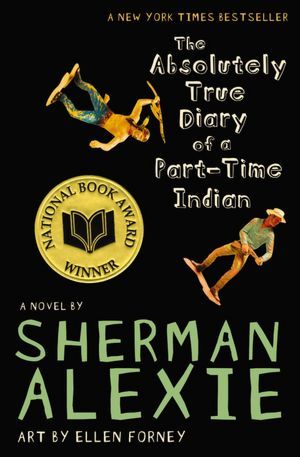

5. “The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian” by Sherman Alexie

- Sherman Alexie’s young adult novel has been banned from some school districts for sexual content. It’s the story of a Native American teenager who leaves his reservation to attend an all-white school. This is a good one for teens to read because it explores ideas of self-discovery and independence while also showing an important account of growing up indigenous in a predominantly white space. (Age 13+)